We get letters

In late February of this year, we received word that an advertising company, ironSource, had obtained a leaked draft of our paper on COPPA violations in Android apps. In that version of the paper, we mentioned them (and their subsidiary, Supersonic) exactly once: in a table of advertising SDKs whose terms of service prohibit their use in child-directed apps (Table 2 of the final paper). We noted that many third-party SDKs include these clauses presumably because they do things with the received data that would violate COPPA, such as user profiling or behavioral advertising.

The point of this analysis was to show that app developers are systematically violating these contractual obligations. For instance, we noted that ironSource receives personal data from 466 unique child-directed apps.

On April 9, we received a letter from their general counsel (below). This letter came three days after our paper was published online, six weeks after we first became aware that they possessed an unauthorized copy, and five weeks after they changed their privacy policy to remove the clause cited in our paper.

Background on ironSource

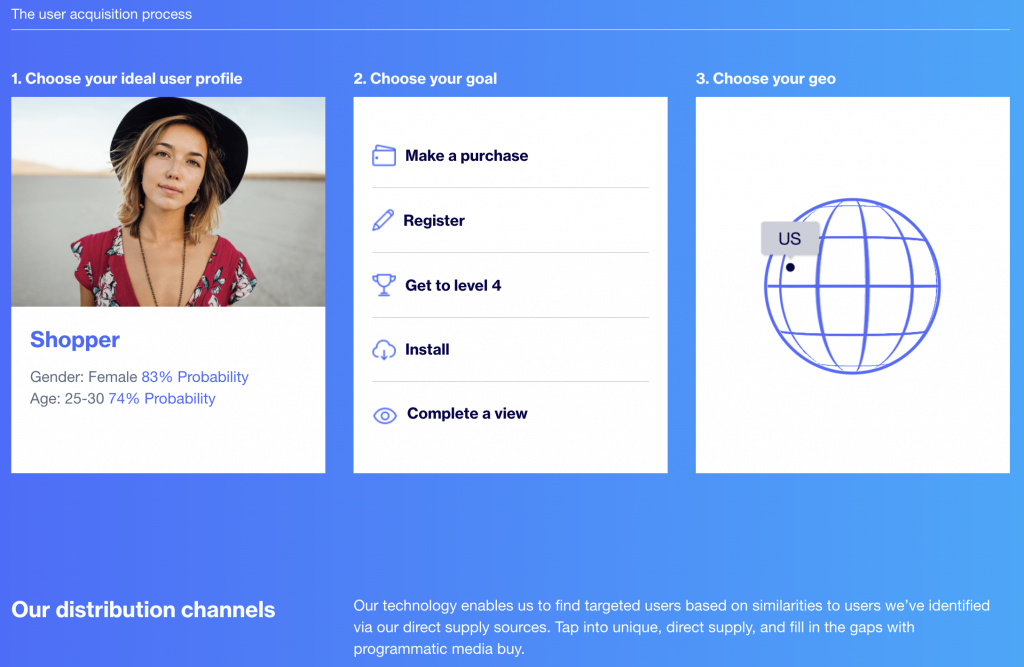

ironSource is a mobile advertising company, which seems to specialize in highly targeted ads. Here is a screenshot from their website:

Performing this type of profiling and targeting is very likely to violate COPPA, if it is being done within apps that are directed at children under 13. This is likely why ironSource (and many other companies in this line of work) include clauses in their terms of service to prevent developers of kids’ apps from using their software. In the paper, we demonstrated that these clauses seem to be systematically violated (e.g., we observed 466 child-directed apps transmitting personal data to ironSource), and these terms don’t seem to be enforced by the SDK providers.

ironSource’s Privacy Policy

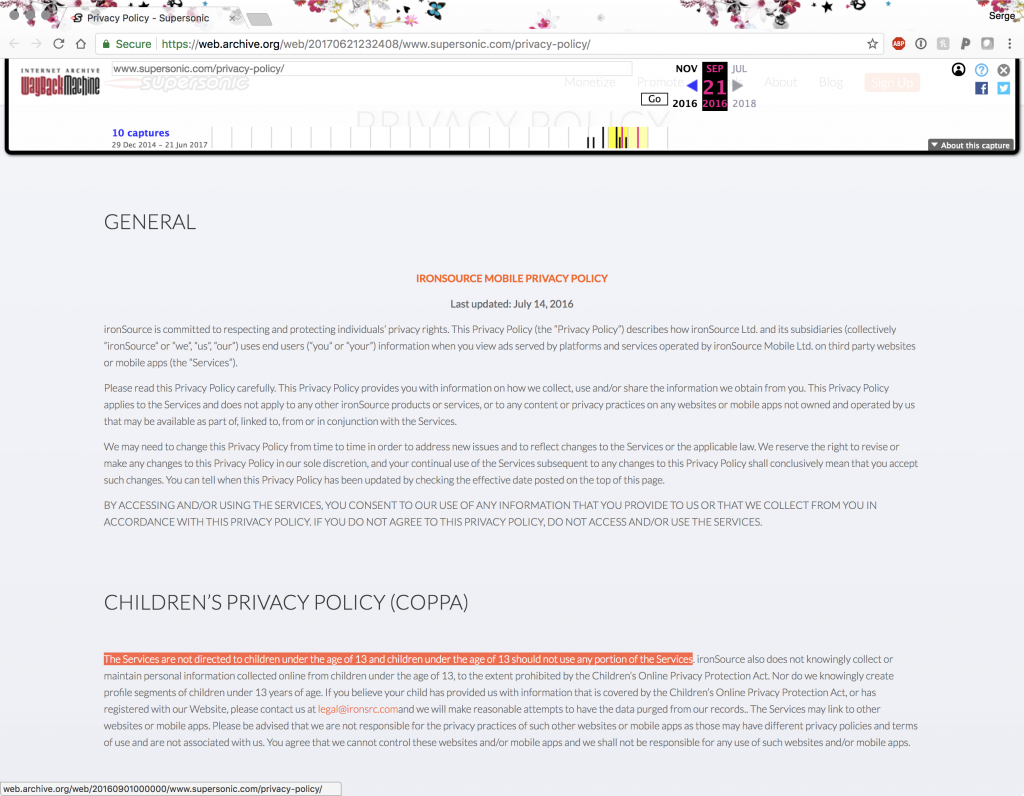

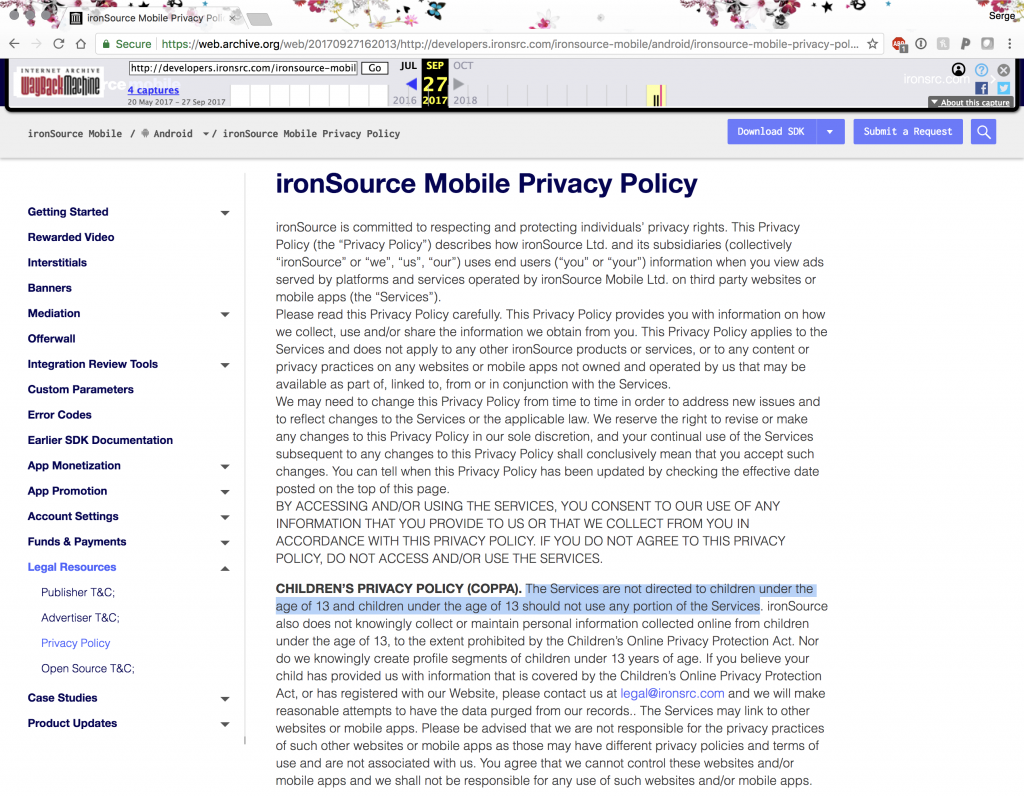

At the time that we submitted the paper for publication (November 2017), this was the language in ironSource’s privacy policy concerning children (emphasis mine):

CHILDREN’S PRIVACY POLICY (COPPA). The Services are not directed to children under the age of 13 and children under the age of 13 should not use any portion of the Services. ironSource also does not knowingly collect or maintain personal information collected online from children under the age of 13, to the extent prohibited by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. Nor do we knowingly create profile segments of children under 13 years of age. If you believe your child has provided us with information that is covered by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, or has registered with our Website, please contact us at legal@ironsrc.com and we will make reasonable attempts to have the data purged from our records.. The Services may link to other websites or mobile apps. Please be advised that we are not responsible for the privacy practices of such other websites or mobile apps as those may have different privacy policies and terms of use and are not associated with us. You agree that we cannot control these websites and/or mobile apps and we shall not be responsible for any use of such websites and/or mobile apps.

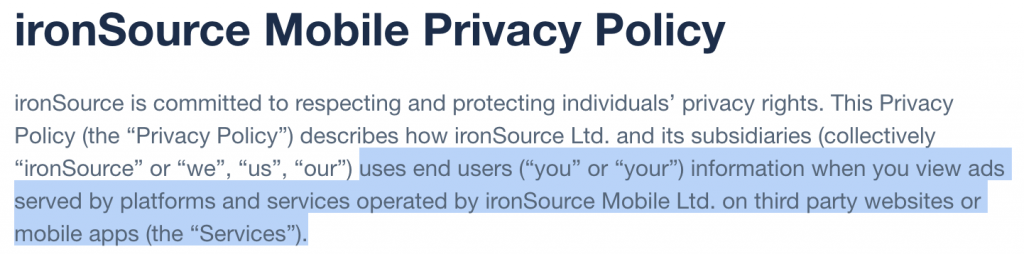

At the top of the policy, “Services” is defined as (again, emphasis mine):

This Privacy Policy (the “Privacy Policy”) describes how ironSource Ltd. and its subsidiaries (collectively “ironSource” or “we”, “us”, “our”) uses end users [sic] (“you” or “your”) information when you view ads served by platforms and services operated by ironSource Mobile Ltd. on third party websites or mobile apps (the “Services”).

Here is a screenshot of the policy from the Wayback Machine:

Thus, the policy indicates that children under 13 should not be allowed to see ads served by ironSource in mobile apps. How can a developer make sure that “children under the age of 13 should not be using any portion of the Services”? By not including ironSource’s SDK in child-directed apps.

In the paper, we cited Supersonic’s version of the privacy policy (since most of the traffic we observed was going to supersonicads.com, which is a subsidiary of ironSource). However, this language was also present in ironSource’s privacy policy in their developer documentation:

Thus, our citation of this policy was accurate at the time that we wrote the paper. For reasons that will become apparent below, when citing online sources, always include an “accessed on” date in you bibliography! (And to be extra safe, also save an offline copy.) In the paper, we reported that the above language was found in ironSource’s privacy policy as of September 29, 2017.

ironSource’s Letter

On April 9, 2018, Irwin (the paper’s first author) received the following letter:

Letter from ironSourceTo our surprise, between first receiving a leaked draft of our paper in February and sending this letter in April—presumably while they waited for the paper to appear online, for plausible deniability, so that they would not have to explain how they came into possession of a stolen draft—ironSource updated their privacy policy to remove the clause about children not using their services. The current policy, dated March 4, 2018 (i.e., after they were aware of the paper), now simply says that they have no knowledge of receiving data from children.

Ms. Litay, who claims to be a lawyer, claims that our paper is incorrect because it cites a clause that was removed after the paper was written! This requires significant mental gymnastics (or a significant amount of chutzpah and the misguided belief that the recipients of her letter do not know that the web is archival).

Her letter also says that this policy only governs data received from developers who sign up to use ironSource’s SDK, and not end-users who are shown ironSource’s ads in mobile apps. Again, this is contradicted by literally the second sentence of both the privacy policy quoted in the paper (the definition of “Services” quoted above), as well as the current version (dated March 4, 2018):

Their new privacy policy seems to approach COPPA compliance by simply stating that they have no knowledge of personal data collected from children, and leaving it at that. I’m a little confused as to how this can be the case, when her letter admits that all app developers must submit information about their apps to ironSource, prior to using the SDK. That is, ironSource collects both developer names and app names from every app using their SDK. Looking at just our dataset for all the apps transmitting personal information to ironSource, several developers’ names include words like “child,” “baby,” or “kids.” (Not to mention that every transmission to ironSource from an app also includes that app’s package name, which will also include these words.)

Thus, if they know that they are receiving personal data from apps with the word “kids” in their names, how can they claim to not knowingly receive data from children or child-directed apps?

Our Response

After consulting with the Office of General Counsel at U.C. Berkeley, I sent the following response this week:

ironSource Response